The Viola Music of John Williams

The Viola Concerto and the Duo Concertante

After the concertmaster of my orchestra suggested that we play duets together, I set out to amass a collection of repertoire for violin and viola, starting with the standards: the Handel-Halvorsen Passacaglia in G minor, Martinů’s Three Madrigals, and the volumes by Mozart, Rolla, Stamitz, and both Haydns. In a few cases I gave in to the temptation to order an unfamiliar work by a well-known composer; for example, I was unaware that Jean Sibelius had composed a duo for violin and viola, but when I saw it listed in an online catalogue I added it to my shopping cart without hesitation. As it happens, however, this duo is an early work, a rather uninspired minuet and trio written as a pedagogical tool when the composer was a struggling young violin teacher in his twenties, with no hint of the grandeur and sophistication of his later symphonies and tone poems. It may turn up on the odd student recital purely because of the composer’s celebrity, but I doubt that it will impress anybody.

Yet I was even more intrigued to discover, in the same catalogue, a duet for violin and viola by a composer of even greater celebrity than Sibelius: the Duo Concertante by John Williams. Yes, that John Williams. Not John Williams the classical guitarist, and not John Williams the jazz drummer, but the latter’s son and namesake: John Williams, the most celebrated film composer of all time.

If there is any living composer who needs no introduction, it is Williams. In his six decades in the entertainment industry his music has been key to the success of many of Hollywood’s most popular films: all of the Star Wars movies, the Indiana Jones series, the first three Harry Potter films, both Home Alone films, Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, E. T.: the Extraterrestrial, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, and dozens more. Because of his long association with directors Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, eight of the twenty highest-grossing blockbuster films of all time have Williams scores, and his Star Wars soundtrack album is by far the best-selling recording ever made by a symphony orchestra. As principal conductor of the Boston Pops from 1980 to 1993 (and now the orchestra’s laureate conductor), he popularised the use of film scores – his own as well as others’ – as concert programming. No other composer in history has won more awards, or earned as great a fortune, for writing orchestral music, and none has garnered a larger audience for it. Hardly a person alive today has not heard his music, and even fewer orchestral musicians have never played it.

Less familiar is Williams’s body of concert music. Of his mere handful of chamber works, the Duo Concertante is the only one to feature the viola. Apart from a symphony written in 1965, most of his orchestral works are brief fanfares or overtures composed for specific occasions, such as the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. His most significant large-scale works are the dozen-odd concertos he has written, most of them since the beginning of this century, for nearly every instrument of the orchestra – including a Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, which Williams composed in 2007 at the age of seventy-five. Given his towering achievements as a composer, his contributions to the literature for our instrument should be of keen interest to all of us.

I developed an appreciation for the music of John Williams at a very early age, thanks to his scores for the Irwin Allen science-fiction adventure TV series The Time Tunnel, Land of the Giants, and especially Lost in Space, which was by far my favourite show as a child. Lost in Space debuted in 1965, a year before Star Trek, and over the years has been derided by fans of the latter show for its ludicrous storylines, absurd rubber-suited monsters, and above all the insufferably effete villain Dr. Zachary Smith. But among its compensating virtues – an appealing family of heroes, a vibrant colour palette, and the coolest robot in the entire history of science fiction – one stands supreme: Lost in Space had the greatest music ever written for a television series. Williams composed its theme music as well as over an hour’s worth of musical cues that were recycled into all 83 episodes of the series. It was John Williams, long before I ever heard a movement of Beethoven or Tchaikovsky, who first made me appreciate the stirring dramatic power of the symphony orchestra.

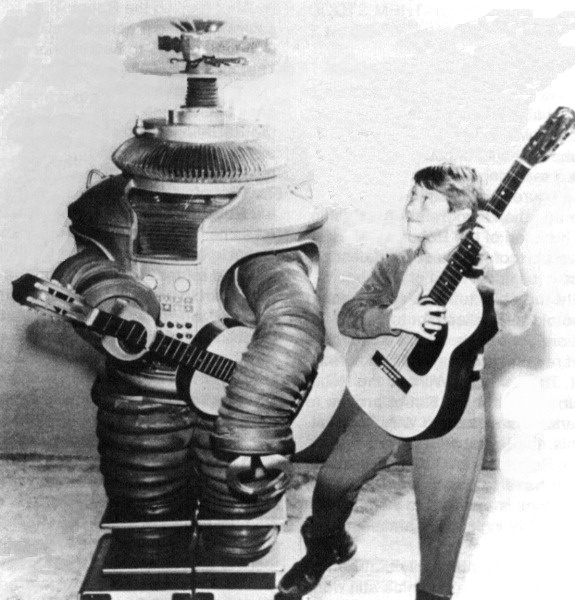

An earlier Duo Concertante by John Williams, for left- and right-handed space guitars, has been lost.

Williams began composing for television at a fortuitous period in Hollywood history. By the 1960s, after a decade of attempting to lure viewers away from their TV sets with unprofitable gimmicks such as 3-D and Cinemascope, the major film studios had adopted an attitude of “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” and opened television divisions of their own. Their well-financed music departments were staffed by a new generation of highly talented composers and arrangers who could keep pace with the hectic schedules of television production. At the same time, the musicians’ union was extremely powerful in Hollywood. The studios maintained full symphony orchestras whose musicians were eager to earn overtime and doubling pay, which is why Hollywood television scores of that era are replete with solos for auxiliary woodwinds; hardly an episode from any show of the sixties, from The Twilight Zone to Bonanza to The Flintstones, does not have at least one bass clarinet solo in it. The union’s power ultimately undermined its successes; by the seventies, studios had begun to outsource their music production overseas, leading to, among other things, Williams’s long and fruitful association with the London Symphony Orchestra. But he had the good fortune to enter the field during a heyday of symphonic scoring that, in television at least, will most likely never come around again.

Just as the Hollywood studios were pouring greater resources into the music for their television productions, they were turning away from traditional orchestral soundtracks in their feature films; and nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of science fiction. Directors of science fiction films desired that the musical score, above all, convey a sense of menacing otherworldliness, for which the new genres of postwar modernism and electronic music were admirably suited. In his score to The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), composer Bernard Herrmann not only employed an “orchestra” consisting of two theremins, electric guitar, electric bass, electric violin, three organs, four pianos, four harps, and enormous brass and percussion sections, but also used reverse recording techniques and frequency modulation to express the fearful uncertainty of the early Atomic Age. The fully electronic soundtrack to Forbidden Planet (1956) was so outré that the studio credited composers Louis and Bebe Barron with “Electronic Tonalities,” rather than music.

Modernist musical cues from stock music libraries became so overused in low-budget science fiction films that by the late sixties directors began to consider other alternatives. For the science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), director Stanley Kubrick rejected an original score composed by Alex North in favour of a soundtrack made up of orchestral standards like Also Sprach Zarathustra and The Blue Danube Waltz; while in that same year, Roger Vadim’s Barbarella grooved and bopped to the hip psychedelic pop sounds of the Bob Crewe Generation.

For Lost in Space Williams furnished a futuristic setting with music grounded in the traditions of the past, a neo-Romantic style based on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century orchestral and operatic antecedents. “It was not the music that might describe terra incognita, but the opposite of that,” he told Film Monthly in an interview, “music that would put us in touch with very familiar and remembered emotions.” In so doing Williams almost single-handedly revived the grand, melodramatic, leitmotivic tradition of film scoring epitomised by his idol Erich Wolfgang Korngold (best remembered for his music to the Errol Flynn swashbucklers of the thirties), which had held sway in cinema from the beginning of the silent era. Easily apprehended by television audiences, his music for Lost in Space not only enhanced the dramatic action on screen, but hyperbolically exaggerated it. As a small child I was highly conscious of its effect; my sister and I would even hum the musical cues as we played out our favourite scenes from the show. It likewise had a profound effect on the young director Steven Spielberg, an avid clarinettist as well as a collector of classic film soundtrack albums, making him eager to meet (as he told his biographer Joseph McBride) “this modern relic from a lost era of film symphonies.” The rest, as they say, is history.

One strength of Williams’s film music is his clever use of recognisable referents, and occasionally direct quotations, from great orchestral works. In fact, for lovers of classical music, a big part of the fun of watching a movie with a John Williams score lies in identifying the musical Easter eggs that he has interspersed throughout the soundtrack. The score to Star Wars, for example, contains references to The Planets, The Rite of Spring, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Siegfried, and Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony, among others. The first phrase of the love theme in Superman is lifted verbatim from Strauss’s Tot und Verklärung, and the opening title to Home Alone (which takes place during Christmastime) pays homage to Tchaikovsky’s Petite ouverture from The Nutcracker. At one poignant moment in Schindler’s List, Williams quotes the opening of the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, inserting a single non-harmonic tone into a chord to create an effect of searing tragedy.

Thus it should come as no surprise that his Viola Concerto owes a direct debt to well-known Romantic and post-Romantic works in the literature for viola and orchestra, particularly the Walton Concerto. (Williams clearly has a affinity for Walton, who composed music for no fewer than thirteen feature films; the Star Wars Coronation March is largely modelled on Walton’s 1953 coronation march Orb and Sceptre.)

In 2003 Williams conducted the Boston Pops in a performance of Alan Shulman’s Theme and Variations for viola and orchestra with soloist Cathy Basrak, principal violist of the Pops as well as assistant principal violist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (The Pops has the same personnel as the BSO, minus the latter’s section leaders.) Impressed by her artistry, Williams “resolved to write a work, not only for an instrument I love,” as he states in the score, “but to celebrate the brilliance of this great violist.” Four years later, Williams presented Basrak with his completed Viola Concerto. The premiere took place on 26 May 2009 in Boston’s Symphony Hall, on a program otherwise consisting almost entirely of Williams’s film music.

Generally I resist the temptation, indulged in by so many music critics, to describe a new musical work by comparing it to other, better known ones; but in the case of the Williams Viola Concerto, there are so many similarities to the Walton that I cannot avoid it. Like the Walton, the Williams is scored for large orchestra and is in three movements, with the fastest, and shortest, one in the middle; this was a revolutionary scheme for a concerto when Walton first employed it in 1929 but has since become, if not quite the norm, then certainly commonplace among viola concertos, for example those of Alan Hovhaness and Brett Dean. Like the Walton, the Williams concerto begins with a brief, soft orchestral introduction establishing a minor key (B minor here, the key of the Shulman, rather than Walton’s A minor) before the viola solo enters with a lyrical melody on the D string. The theme is developed, often in canon with woodwinds, then gives way to a brassy tutti which would not sound out of place either in a Williams film score or in Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast. A second lyrical theme, whose character contrasts very little with the first, follows, with further development of the tutti. Over a quarter of the movement – a full three minutes – is given over to the cadenza, rhapsodic and contemplative rather than virtuosic and extroverted. A brief recapitulation of the opening theme is followed, believe it or not, by another, shorter cadenza. The movement ends softly – again, like the Walton – on a minor tonic chord superimposed over a major one.

The solo viola kicks off the brisk scherzo with a moto perpetuo in constantly changing metre, punctuated by syncopated rhythms in the orchestra. In the middle of the movement is a droll duo for solo viola and timpani, humorously titled “Family Argument,” acknowledging Basrak’s husband and colleague, Boston Pops timpanist Timothy Genis. (At Basrak’s request, Williams revised the passage so that the viola not only has more to say, but also has the last word.) Of course, this is not the first viola concerto to feature a dialogue between viola and timpani; the Dellamaggiore/Peter Bartók version of the Bartók Concerto opens with one.

The third movement is the emotional heart of the work, a tender arioso wholly unlike the stately, contrapuntal finale of the Walton concerto. Much of the movement is a colloquy between viola and harp, a passage Williams dedicated to Boston Pops principal harpist Ann Hobson Pilot, who retired at the end of the 2009 season after forty years with the orchestra. Williams stipulates in the score that the harpist should be situated in front of the orchestra, next to the viola soloist. (This, too, is not without precedent in the viola literature; Berlioz made the same stipulation in Harold in Italy.) The orchestra writing is effective and economical, spare and transparent, rising to forte only in the one brief tutti. The ending of the concerto recalls that of the Shostakovich Sonata, with the solo viola holding a long E (here, a high harmonic) as the accompaniment gradually comes to rest on a tranquil C major chord.

All of these referents bring to mind the charge of unoriginality that over the years has been levelled against Williams for both his film scores and his concert music. “It has long been fashionable,” wrote Alex Ross in the New Yorker, “to dismiss Williams as a mere pasticheur, who assembles scores from classical spare parts. Some have gone so far as to call him a plagiarist.” Yet there is nothing inherently wrong with using great musical works as models, inspiration, and even source material; all composers do this to some extent. What inspired a work in the first place matters less than whether it stands on its own merits. The similarities between the viola concertos of Williams and Walton, though obvious to any violist, would matter little to concertgoers in general; and at any rate Williams deserves to be applauded for having taken the trouble, as he clearly did, to gain a better understanding of the viola’s capabilities as a solo instrument by studying the great works in its literature.

So why is the Williams Viola Concerto not better known? It is not the kind of concerto that is likely to bring an audience cheering to its feet – few viola concertos are – but it could bring smiles to their faces and tears to their eyes. It is no less difficult than the Walton concerto, but no more so either. The solo viola part with piano reduction is available through most online catalogues and costs less than $20US – a pittance for a modern concerto. Given the composer’s fame, and the eagerness of orchestras the world over to program his music, there is no reason that the Williams should not quickly become standard repertoire, appearing at least as often as the Walton or the Bartók on concert programs and even audition lists: the first great viola concerto of the twenty-first century.

Yet for reasons I do not fully understand, the Williams Viola Concerto has been but rarely performed since its premiere in Boston eight years ago. (By contrast, William Primrose performed the Bartók concerto over a hundred times in the decade following its premiere in 1949.) Perhaps because his film scores have become part of the fabric of our culture and, so to speak, belong to the world, Williams is very possessive of his own music and stringently controls where, when, and under what circumstances his music may be performed or recorded. The scores and orchestra parts to all of his concertos are kept in his personal library, and he will only lend them out to musicians whom he knows and trusts. His friend Michael Zaretsky, for example (see below), was granted the honour of performing the Viola Concerto at the Peninsula Music Festival on Lake Michigan in the summer of 2010. On the other hand, when the Kentucky Symphony Orchestra gave a John Williams concert some years ago, our plans to program his Horn Concerto were summarily quashed. (We were also forbidden from playing any of his music from Lost in Space, which was a grievous disappointment for me personally, but in that case there may have been copyright issues beyond Williams’s control.) Ordinarily composers will cheerfully go to great lengths to secure performances of their music, but then Williams is no ordinary composer.

As of this writing [June 2017], John Williams is eighty-five years old and still going strong as both composer and conductor, currently working on the score to the eighth instalment in the Star Wars series; and I hope he has many happy, healthy, productive years ahead of him. What the future holds for his Viola Concerto is impossible to guess. It is a beautiful, moving, virtuosic work by a composer of widespread popularity, a work that ambitious violists will want to learn and orchestra programming committees would enthusiastically endorse. I would not say that it stands with the Bartók and Walton concertos as a masterpiece, but it could very well become as much of an audience favourite as the Korngold Violin Concerto – if only Williams will let it happen.

As for the Duo Concertante, it, like the Viola Concerto, was inspired by a particular work Williams heard performed by his orchestral colleagues in Boston. In 1997 Williams attended a prelude concert (a brief program of chamber music immediately prior to an orchestra concert) at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony’s summer home, and was greatly impressed by the Three Madrigals of Martinů, which he had never heard before. After the concert he congratulated the performers, BSO violinist Victor Romanul and violist Michael Zaretsky, and told them of his fascination with the possibilities of that instrumental combination. Seeing an opportunity, Zaretsky asked Williams if he would consider writing a duet for violin and viola himself; but the composer declined, being, as usual, much too busy with his film work. Nevertheless, in October 2006 Zaretsky was surprised to receive a package from Williams containing the Duo Concertante’s finished score. He and Romanul premiered the work on 17 August 2007 at a Tanglewood prelude concert that also included the Martinů, as well as the Mozart G major Duo K. 423.

Zaretsky expects the Duo Concertante to take its place alongside Martinů and Mozart in the standard repertoire for violin and viola. “This is a real gift,” he told Williams, “not to me, of course. It’s a gift to all viola and violin players.” Be that as it may, it is not necessarily a gift that all of us can use. Before the Tanglewood premiere, Zaretsky and Romanul spent three hours workshopping the piece with Williams as the composer made adjustments to the score. They should have taken much longer, for the published score and parts are in dire need of editing. The main problem with the Duo Concertante, and the feature that distinguishes it most starkly from Three Madrigals, is that while Martinů, a capable violinist who spent three years in the Czech Philharmonic’s second violin section, wrote idiomatically for strings, Williams, a pianist and conductor, does not.

The duo begins with a chorale of quadruple-stop chords in both instruments, at least one of which cannot possibly be played on all four strings of the viola; there are ways to approximate the effect, but the chord would have to be written out differently to make it clear. The wide melodic leaps in the first movement, covering the entire range of the viola, require constant string crossings and shifts of position, all of them awkward. In bars 33 and 34 the viola part contains a couple of first/fourth finger unisons that are as unnecessary as they are unplayable. The second movement, like that of the Martinů, ends with a passage of densely textured fingered tremolos, but it is unclear whether Williams occasionally wants them to be combined with bowed tremolo, or whether the slurs have been omitted by mistake. The final movement at least has something of the restless rhythmic energy that characterises Martinů’s best music, but the other two tend to ramble: the first with its meandering, modulating scales, and the second with its senza misura cadenzas.

I was introduced to the Mozart and Martinů duos as a student, but the Williams Duo Concertante would have been beyond me at that time, and I fear that it still may be. I would need many hours to work out bowings and fingerings, and I suspect that I would have to subject more than a few passages to an editing so thorough that it bordered on revision. If it were up to me alone, I would be sorely tempted to do so; I have loved the music of John Williams all my life, am always keen to expand my repertoire, and seldom shy away from artistic challenges. But my violinist friend has made it clear that she is unwilling to put that much time and effort into the Duo Concertante, and, truth be told, I cannot blame her.

In the meantime, we have had a jolly time with our duets, performing Mozart, Martinů and Handel-Halvorsen at multiple venues. At present we are working on the Opus 1 duos of Johann Andreas Amon, a classical composer who among other things composed two viola concertos, both with scordatura tuning; and the Divertimento, Opus 37 no. 2, by Ernst Toch, a Viennese modernist who fled Hitler’s Europe to become a successful film composer in Hollywood. But we will not be tackling the Duo Concertante of John Williams.

“Oh, the pain... the pain!”

As Dr. Smith of Lost in Space might have put it, my poor back is much too delicate to bear the burden of such an arduous undertaking. It pains me greatly to spurn this “gift” from a composer whose music thrilled me at a tender and impressionable age, its symphonic bombast transporting me to new and wondrous worlds of the imagination. For over half a century John Williams has had the privilege of working with nothing less than the world’s finest musicians, whether in the concert hall or the recording studio. It will be for virtuosos of this calibre – the true Jedi Knights of the viola – to give voice to this unique work by a man whose music has touched so many hearts, and whose artistry will be only more deeply appreciated with the passing of time.

As Dr. Smith of Lost in Space might have put it, my poor back is much too delicate to bear the burden of such an arduous undertaking. It pains me greatly to spurn this “gift” from a composer whose music thrilled me at a tender and impressionable age, its symphonic bombast transporting me to new and wondrous worlds of the imagination. For over half a century John Williams has had the privilege of working with nothing less than the world’s finest musicians, whether in the concert hall or the recording studio. It will be for virtuosos of this calibre – the true Jedi Knights of the viola – to give voice to this unique work by a man whose music has touched so many hearts, and whose artistry will be only more deeply appreciated with the passing of time.

May the Force be with them!

The Concert for Viola and Orchestra and the Duo Concertante are both published by Hal Leonard as part of the John Williams Signature Edition series.

Victor Romanul and Michael Zaretsky have released a two-disc CD of duos for violin and viola, including the Williams Duo Concertante, on the Artona label. It is also available for download.

A bootleg video of the premiere of the Williams Viola Concerto with Cathy Basrak and the Boston Pops has been posted on YouTube, but the sound quality is very poor. There is, however, a very fine performance on YouTube of the reduction for viola and piano with Adelaide-born violist Víctor de Almeida and pianist Mitsuko Morikawa.